In late 1959, the Saskatchewan government sponsored a meeting on co-operative housing in Regina. One of the conclusions that the participants reached was that it took at least five years to develop co-operative housing. They also recognized that it would be very difficult for “the people who need and want housing” to hold a group together for that long. What was needed was a larger organization, one that would develop housing co-operatives and then recruit residents. It is, of course, one thing to identify a need. It is a completely different thing to fill it.

Two of the people at that meeting in Regina were Skapti (Scotty) Borgford, an engineer who had switched from teaching at the University of Manitoba to work with a local architectural firm, Green, Blankstein, Russell Associates, and Dan Slimmon, who worked for the Manitoba Co-op Wholesale. [1]

On their return, they invited fifteen people to a meeting in the lunchroom of the Manitoba Honey Producers to “discuss the need for—and the possibility of Co-op Housing in Manitoba.” Alex Laidlaw, the secretary of the Co-operative Union of Canada and a director of the Central Mortgage and Housing Corporation, was a featured speaker at the meeting. In issuing the invitation, Slimmon wrote “it may surprise you to know that CM & HC encourages Co-operative Housing development.” [2] Laidlaw, who had worked with Moses Coady in the Antigonish Movement, certainly was a strong supporter of co-operatives. CMHC’s commitment to co-operatives was, however, to remain suspect. [3]

At the meeting, a committee was struck to study the prospect of co-operative housing in Manitoba. The committee, which was headed by Borgford, went much further and it moved quickly. Borgford, one of a number of University of Manitoba professors who attempted to establish a housing co-operative on land on University Crescent in the 1950s, came from a family of builders. His father, an immigrant from Iceland, worked in construction and had sought to bring up all four of his sons to become engineers. In the case of three of them, he succeeded. Like many Icelandic families, the Borgfords lived in the city’s West End, where they adhered to the Unitarian Church. The church’s strong teachings of social responsibility and equality were significant in shaping his children’s choice of work. One of the engineers left the profession to take up a position as a Unitarian minister, while the non-engineer made a significant contribution to the development of the trade-union movement in Western Canada. Aside from making a considerable contribution to his profession and serving as a New Democratic Party school trustee, Scotty was to prove the driving force behind the creation of Canada’s first permanent housing co-operative. [4]

By January 12, 1960, two meetings had been held (one, miraculously on January 1) and two more committees had been struck. According to Slimmon, “Borgford’s drive” was carrying the process forward. (In later years, his commitment would include giving serious consideration to mortgaging his family’s home to provide bridge funding for a co-operative housing project and cancelling his participation in a family trip to Europe.) The organizers quickly came to favour the creation of a “continuing housing co-operative” as opposed to a building co-operative, since in the latter type the “owner may quickly cash in on his savings.” [5] There is no indication that they ever considered the creation of a for-profit co-operative.

The first step was to create a central organization that could serve as a “Mother Hen.” This was based on the Swedish model of housing co-op development in which a “mother” organization established “daughter” co-operatives. The Tenants’ Saving and Building Society (commonly referred to as the HSB) served as an overall umbrella organization in this process. [6] The Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba (CHAM) was incorporated on January 23, 1960. The ten founding members included Borgford, Slimmon, Art Coulter (the secretary-treasurer of the Winnipeg Labour Council), Ruth Struthers (who was active in the Provincial Council of Women), A. W. Wood (University of Manitoba faculty of agriculture), R. Kapilik (of Manitoba Pool Elevators), A.D. Ramsay (future president of the Co-operative Credit Society of Manitoba), T.W. Robinson (the future president of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba), D.J. Wood, and R.F. Penner (of the Co-op Union of Manitoba). The six organizational founding members were Federated Co-operatives Limited, Manitoba Pool Elevators, United Grain Growers, Limited, Co-operative Life Insurance Company, Co-operative Fire and Casualty Company and the Winnipeg and District Labour Council. [7] The drive of individuals such as Borgford and Slimmon was important, but co-operative housing could not have been established without the economic and organizational resources that the broader co-operative movement had developed in the previous half-century.

The founders would have run across each other in co-op stores, Co-operative Commonwealth Federation conventions, and at labour council meetings.

They were working quickly because they wished to seize an opportunity. After decades of delay, the City of Winnipeg had finally committed itself to what was at the time referred to as “urban renewal.” The envisioned project was intended to redevelop the area between Selkirk Avenue and the Canadian Pacific railyards. The first step in this process would be the creation of low-income housing in the northwest corner of the city (which was referred to at the time at Burrows-Keewatin) to house some of the people displaced by the redevelopment of the Selkirk area. [8]

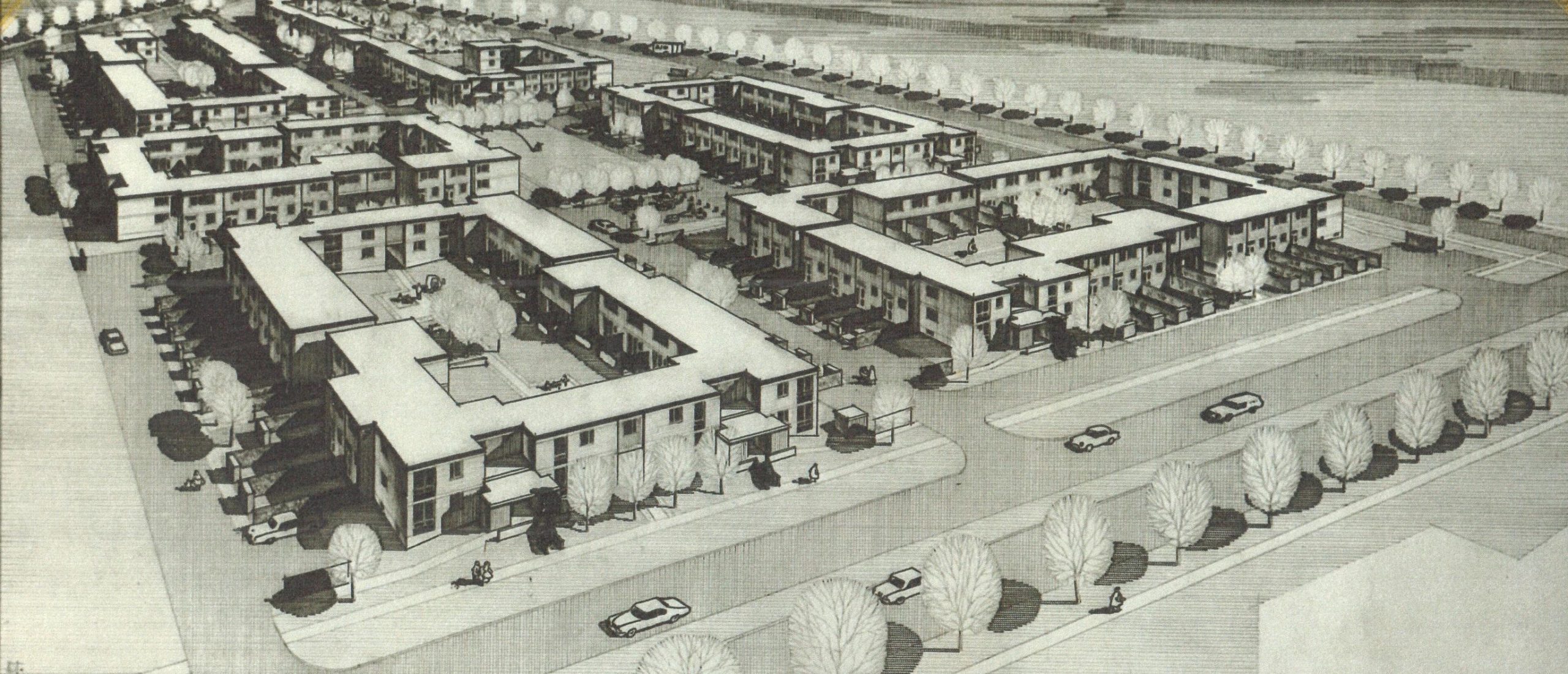

When the city issued a call for proposals for the area, CHAM was ready. With the assistance of the Green, Blankstein, Russell and Associates architectural firm, CHAM had developed a proposal to develop close to 1,000 units of low-cost housing in Burrows-Keewatin. [9]

Initial meetings with the City’s Urban Renewal Board and its housing committee went positively, and planning continued apace throughout the year. [10]

At the beginning of the following year, under the impression that it had the support of council, CHAM unveiled its ambitious proposal: a ten-million-dollar, 980-unit project on 950 acres of land. Included were plans for parks, a shopping centre, senior-citizen housing, and a community centre. The proposal depended on the sale of the land from the city and a 25-year mortgage from CMHC. CHAM’s lawyer, C.N. Kusher told the Winnipeg Tribune that the plan featured “the best features of European low-cost housing and an 80 million [dollar] project in New York City.” [11]

The organizers were particularly impressed with the extensive series of housing co-operatives the labour movement had developed in New York City in the first half of the twentieth century. [12]

The Urban Renewal Board recommended, unless the city were to decide to develop its own public housing in Burrows-Keewatin, it should accept the CHAM proposal. However, the proposal was attacked by Peter Taraska, chair of the city’s finance committee. Borgford described Taraska, as “a confirmed private entrepreneur in a large insurance business,” who strove to “thoroughly condemn the co-operative at both ends.” [13] Taraska opposed the plan because it would only provide housing to a “limited class” of people.” [14] The co-op responded that the city was preparing to repeat the mistakes of earlier housing projects in other jurisdictions by failing to integrate public housing into the type of affordable housing a co-operative could create. [15]

There was one positive outcome of the showdown between Taraska and Borgford CBC commentator Bob Preston noted that the CHAM proposal forced the city to “take a stand on public housing or give-in to the Co-op housing request.” [16] After rejecting the CHAM proposal, the council had to commit itself to public housing. In the spring of 1961, council approved an $8.4-million project intended to house 817 families on the Burrows-Keewatin site. [17] Borgford was suspicious at the time of the size of the city’s commitment, referring to it as a “tongue in cheek” proposal. [18] He was correct, the city only built 165 of the proposed 817 housing units in Burrows-Keewatin. [19] And, in the fall of 1961, when CHAM submitted a scaled-backed proposal, Taraska once more succeeded in blocking the sale of land. [20]

During the course of the year, CHAM had chartered its first “daughter” co-op, the Willow Park Housing Co-operative. Even though it was little more than a name and set of bylaws, 100 potential residents had been recruited. An employee had been hired, and Federated Co-operatives and Manitoba Pool Elevators had guaranteed a third of a million dollars in financing. [21] Persistent lobbying paid off and in April 1962 the city agreed to sell 11.6 acres of land to in the Burrows-Keewatin district to CHAM (in end the land was leased), but it would not be serviced until the following year. Green, Blankstein, Russell Associates did the design work for the Willow Park project, proposing six clusters of 30 to 35 townhouses that would incorporate 17 four-bedroom units, 101 three-bedroom units, 42 two-bedroom units, and 40 one-bedroom units. CHAM then entered into talks with CMHC and issued a call for tenders. [22] The architects had been consulting with local CMHC, but when CMHC’s national office reviewed the design, it asked for it to be scaled back. One of the ongoing problems that CHAM faced was the fact that much of what it was doing was unprecedented: national, provincial, and municipal governments had difficulty fitting the project into existing programs. A special act of the legislature was required for example, for co-op residents to benefit from an existing school-tax rebate. [23]

CMHC provided a $2.3-million 30-year mortgage. The CMHC loan covered 96 per cent of costs: and member shares covered the remaining 4 per cent. Shares prices ranged from $566 for a one-bedroom unit to $899 for a four-bedroom unit. While CMHC had indicated it would provide the mortgage money when the project was half completed, a National Housing Act regulation required that funding be withheld until 50 per cent of the units were occupied. The project might have failed if the Co-operative Credit Society of Manitoba had not stepped in with a $2-million advance that was guaranteed by the Federated Co-operatives (and later the Co-operative Trust of Saskatchewan). [24] Not surprisingly, Borgford concluded that CMHC was “basically a mortgage company run on a business basis by the government and is more interested in maintaining its financial position than in providing experimental housing.”[25]

Construction, which was expected to last for fourteen months, started in September 1964. At the sod-turning, Borgford said the project was intended for “the have-nots of Canadian housing—those with too-small incomes to qualify for National Housing Act loans, and “too rich” to qualify for subsidized rental housing.” Willow Park would, he hoped, be a “’guinea pig’ for urban renewal across Canada.’” [26]

Several months into the job, after completing ten units, the contractor stopped work to concentrate on a number of more lucrative winter works jobs. [27] At one point during the construction, the city’s building trades unions threatened to shut the job down because it was not being built by union labour. Borgford countered that the house construction sector was non-unionized and all similar jobs were done by non-union labour. There were also conflicts between the co-op and the contractor over the finish and the quality of the work: in some cases, workers lacked the skills for the work they were doing or left the work incomplete, most famously with some plumbing fixtures not being fully connected. [28] Construction dragged on for 26 months, with completion at the end of October 1966. [29] The initial residents lived in a construction zone for over a year. When the project was completed in August 1966, CHAM turned it over to Willow Park Housing Co-operative. [30] The 200-unit co-op was governed by a nine-member board elected by members on a one-vote per household franchise. Board members served for three years and were elected at the co-op’s annual meeting. [31]

Recruiting a sufficient number of members was also a problem: four people were hired to sell memberships on a commission basis, but this fell afoul of government regulations regarding the licensing of salespeople. The number was reduced to two, but it was not sufficient. Flyers were stuffed into grocery bags in co-op stores, ads were taken out in co-op newspapers, daily newspapers, and radio stations. Direct mail solicitation was sent to certain neighbourhoods and 5,000 brochures were distributed. [32] When the grand opening was held in August 1966 the project was three-quarters empty. [33] That summer, Co-op president A.D. Ramsay was feeling particularly beleaguered: sales remained slow, CMHC was still refusing to flow funds, Federated Co-op needed to get some of its money back, the existing co-op members were more interested in advancing individual complaints than acting as members of a co-operative, their contractor was trying to shake them down for an extra payment. Ramsay wrote that he sometimes wondered “how I ever got into all the work and strain this development has created.” [34] It was not until February 1967 that the co-op achieved full occupancy. [35] But interest continued: By 1968 there were fifty families on the waiting list. [36]

A CHAM newsletter article noted that in 1961, the project’s critics kept on trying to figure out what was in it for the proponents. “They keep looking for the gimmick. Someone, somewhere must be making a haul, they say; but they can’t put their finger on it.” [37] When Ramsay was going through his dark moments in the summer of 1966, he consoled himself with the thought that Willow Park “will be a success and will set an example of what can be done and will make future developments much easier.” [38] He was correct: the Willow Park example led to the creation of the Co-operative Housing Foundation of Canada (created by the co-operative movement, the labour movement, and the student movement), a series of government-funded pilot projects, and, in 1973, the establishment of a national co-operative housing program that, until its elimination in 1993, created thousands of units of co-operative housing across the country. CHAM, under Borgford’s direction, played a major role in the development of the co-ops developed in Manitoba during that period. [39]

The people who created Willow Park were convinced that they were creating for the future. And they were correct. By building non-market housing that could not be sold for a profit, they created housing that would remain affordable for low-income people, even when housing prices went insane. The enduring benefit of co-op housing can be seen when one compares the 1963 Willow Park share prices and housing charges with the 2020 Willow Park share prices and housing charges. In relative terms it is now, far more affordable, to purchase shares in Willow Park, while, once inflation is taken into account, there has been no increase in monthly living expenses.

Bibliography

Ames, J. W. “Co-operative Housing in Sweden.” The Irish Monthly 77, no. 913 (1949): 310-20.

Borgford, Brian. Gil. North Charleston, South Carolina: Creatspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013.

Borgford, S.J. Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper.

Davis, Vicki L. “Alexander Fraser Laidlaw”. The Canadian Encyclopedia, 15 December 2013, Historica Canada. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/alexander-fraser-laidlaw. Accessed 02 September 2020.

Finnigan, Harry. “The role of co-operative housing resources groups in Canada: A case study of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba (C.H.A.M.).” unpublished Master of City Planning Thesis, Department of City Planning, University of Manitoba, 1978.

Freeman, Joshua. Working Class New York: Life and Labour Since World War II. New York City: New Press, 2000.

Gregory, Bruce. “Willow Park: A study in co-operative home ownership.” Unpublished paper, abridged, University of Winnipeg, March 1971.

Slimmon, Don. People and Progress: A Co-op Story. Brandon: Leach Printing, undated.

Footnotes

[1] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966,S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 2. Interview with Karen Botting, July 28, 2020; Don Slimmon, People and Progress: A Co-op Story, Brandon: Leach Printing, undated, xiii–xv; Don Slimmon, People and Progress: A Co-op Story, Brandon: Leach Printing, undated, xiii–xv.

[2] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, D.H. Slimmon to S.J. Borgford and others, November 2, 1959.

[3] Vicki L. Davis, “Alexander Fraser Laidlaw,”. The Canadian Encyclopedia, 15 December 2013, Historica Canada. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/alexander-fraser-laidlaw. Accessed 02 September 2020.

[4] Family background information from interview with Karen Botting, July 28, 2020; Winnipeg Architectural Foundation, “Skapti ‘Scotty’ Josef Borgford, https://www.winnipegarchitecture.ca/skapti-borgford/, accessed September 4, 2020. Gil Borgford’s story is recounted in Brian Borgford, Gil, North Charleston, South Carolina: Createspace Independent Publishing Platform, 2013.

[5] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, Co-operative Union of Manitoba, A Progress Report on Co-op Housing, January 12, 1960; Interview with Karen Botting, July 28, 2020.

[6] J. W. Ames, “Co-operative Housing in Sweden,” The Irish Monthly 77, number 913, 1949, 312–314.

[7] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 2. For A.D. Ramsay biographical information, see: “Proclamation,” Brandon Sun, October 21, 1966; For Ruth Struthers biographical information see: Gordon Goldsborough, “Ruth Heyes Struthers,” Manitoba Historical Society, Memorable Manitoban, http://www.mhs.mb.ca/docs/people/struthers_rh.shtml , accessed August 27, 2020; for R. Kapilik, see: “Pool meet opens,” Winnipeg Free Press, October 30, 1962; for R.F. Penner see: “25 Manitobans leave for meet,” Winnipeg Tribune, April 12, 1961; for Art Coulter, see: “Political activist a tireless advocate for labour rights,” Winnipeg Free Press, April 12, 2005; for T.W. Robinson, “Co-op housing plan revealed,” Winnipeg Free Press, February 2, 1960.

[8] “Board Sets Area For City Renewal,” Winnipeg Free Press, 29 February 1960.

[9] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966,S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 2.

[10] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, D.H. Slimmon to Gentlemen, February 24, 1960; Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Directors Minutes, February 6, 1960.

[11] “Co-op plans big housing project,” Winnipeg Tribune, January 24, 1961; “Co-op housing plan revealed,” Winnipeg Free Press, February 2, 1960.

[12] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Directors Minutes, January 6, 1961. For information on New York co-operatives, see Joshua Freeman, Working Class New York: Life and Labour Since World War II, New York City: New Press, 2000.

[13] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 3.

[14] “Co-op Bid on Housing Is Rejected,” Winnipeg Tribune, 1 March 1961, “Co-ops Rap Refusal On Public Housing,” Winnipeg Tribune, 2 March 1961.

[15] “Housing boss sees flaws in Burrows-Keewatin plan,” Winnipeg Tribune, March 29, 1961; “He favors ‘integrated’ housing,” Winnipeg Free Press, March 31, 1961.

[16] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, “Co-op housing is down, but not out,” Winnipeg Co-op News, March 13, 1961.

[17] “$8.4 Million Housing Approved by Council,” Winnipeg Tribune, 7 March 1961.

[18] S.J. Borgford to Jack Midmore, March 25, 1962. Personal possession of author.

[19] Garry Lahoda, “5,000 low-rent units urgently needed—city,” Winnipeg Tribune, 27 December 1963.

[20] S.J. Borgford to Jack Midmore, March 25, 1962. Personal possession of author; “We’re not defeated—Co-op,” Winnipeg Tribune, November 30, 1961.

[21] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966,S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 3, 6.

[22] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 4; “The Willow Park Story,” Willow Park News, November 1967. (Personal possession of the author).

[23] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 5.

[24] “The Willow Park Story,” Willow Park News, November 1967; “Important duties for directors,” Willow Park News, November 1967, (Personal possession of the author). B.V. Beehler to C.R. Glydon, November 24, 1967. (Personal possession of the author.)

[25] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966,S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 5.

[26] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, “For immediate release.” Undated.

[27] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966,S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 6.

[28] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 7.

[29] “The Willow Park Story,” Willow Park News, November 1967. (Personal possession of the author).

[30] Bruce Gregory, “Willow Park: A study in co-operative home ownership,” Unpublished paper, abridged, University of Winnipeg, March 1971, 5.

[31] Bruce Gregory, “Willow Park: A study in co-operative home ownership,” Unpublished paper, abridged, University of Winnipeg, March 1971, 5.

[32] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966,S.J. Borgford, Co-operative Housing in Manitoba: The Story of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba and the Development of Willow Park Housing Co-operative in Winnipeg, undated, unpublished paper, 7.

[33] “The Willow Park Story,” Willow Park News, November 1967. (Personal possession of the author).

[34] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, A.D. Ramsay to D.G. Tullis, July 22, 1966.

[35] “The Willow Park Story,” Willow Park News, November 1967. (Personal possession of the author).

[36] Garry R. Lahoda, “A Resident’s View of Co-operative Housing: Economic and Social Values of Willow Park” unpublished, undated paper, 1.

[37] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, “Co-op housing is down, but not out,” Winnipeg Co-op News, March 13, 1961.

[38] Provincial Archives of Manitoba, Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, Papers re: Willow Park Housing Co-operative, P 299, File: Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba, 1959-1966, A.D. Ramsay to D.G. Tullis, July 22, 1966.

[39] Harry Finnigan, The role of co-operative housing resources groups in Canada: A case study of the Co-operative Housing Association of Manitoba (C.H.A.M.) unpublished Master of City Planning Thesis, Department of City Planning, University of Manitoba, 1978.